Khmer AI

New Possibilities for Multilingual Research

Taylor Coplen, Director of Educational Programs

7/10/20253 min read

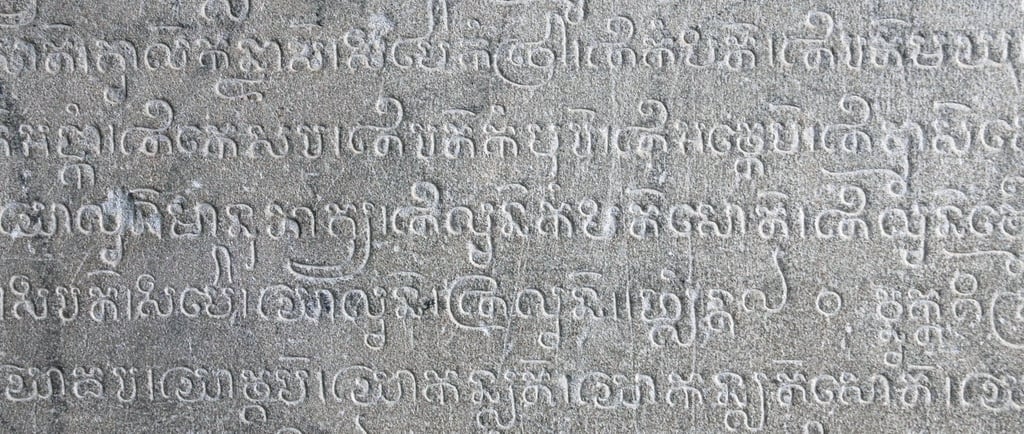

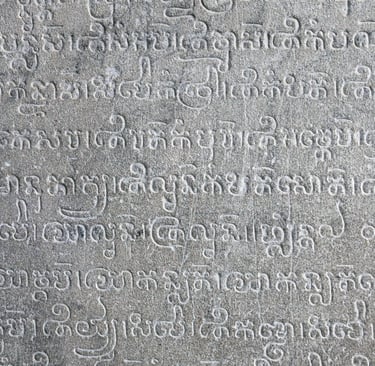

Ever wondered how Khmer language speakers can use"Generative Pre-trained Transformer" AI tools like ChatGPT ? This article explores the transformative role of AI in reshaping how Khmer language and knowledge circulate in the digital age. From ancient script etched into the walls of Angkor Wat to modern machine-readable formats, Khmer is increasingly entering the realm of artificial intelligence.

The Khmer script carved into the sandstone galleries of Angkor Wat has persisted through centuries of environmental erosion and political transformation. It survived French colonial campaigns to Latinize Cambodian writing, periods of national turmoil, and the uneven digitization of non-Latin languages in global computing systems. Today, those same characters are being parsed by neural networks, folded into emerging language models, and indexed by research tools that had long excluded them. What once adorned the sacred walls of a temple complex now circulates in machine-readable form, embedded within the training data of global AI.

This moment is not simply a technical milestone. It reflects a deeper shift in how knowledge travels between languages, systems, and epistemologies. For Cambodian students working across Khmer and English, the rise of AI tools brings both expanded access and heightened responsibility. These technologies can facilitate research across linguistic boundaries, but they also demand critical engagement with the assumptions and limits embedded in each translation, each prompt, each summary.

The tension is visible in classrooms and public debates alike. Over the past year, Cambodian educators, journalists, and government officials have begun to reckon with AI’s role in national development. While the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications has signaled support for AI regulation, public conversations remain focused on familiar concerns: academic dishonesty, data privacy, and the potential erosion of critical thinking. A 2024 study by Mengkorn Pum and Sarin Sok captures this unease, documenting widespread anxiety among teachers and students that AI might shortcut learning or distort understanding, even as both groups begin to experiment with translation tools and writing assistants in everyday academic tasks (Pum & Sok, 2024).

But these concerns exist alongside new capacities. Students who work with Khmer-language sources—newspapers, archival documents, policy reports—can now draw on an emerging suite of tools to support bilingual research. OCR systems trained on Khmer script convert printed documents into searchable text. Language models offer rough English translations or generate summaries that allow for quicker orientation. Students can annotate, critique, and revise these outputs, not to outsource their thinking but to scaffold it. In these workflows, the machine does not replace interpretation; it makes interpretation possible at new scales.

Crucially, the infrastructure behind these tools is no longer entirely external. Cambodia is beginning to build its own AI capacity. Fresh AI, a local startup, allows users to interact with Khmer-language news and public content through chatbot interfaces. Meanwhile, SEA LION AI, a Singapore-based initiative, is developing Southeast Asia-focused OCR and translation tools that include support for Khmer. These initiatives do more than improve performance on linguistic tasks. They shift the center of gravity. Khmer is no longer a peripheral language being translated by foreign systems. It is becoming a core object of technical development in its own right.

This shift has implications for education. When students engage in bilingual AI research, they are not merely consuming knowledge generated elsewhere. They are contributing to a new form of literacy that is linguistic, technical, and political. They learn to question the assumptions embedded in English-language training data. They develop habits of revision and reflection that challenge the authority of the machine. And they begin to imagine new possibilities for how Khmer-language knowledge might circulate in global research conversations.

The risks are real. AI tools still struggle with idiomatic Khmer. OCR errors remain common. Translations can flatten nuance, particularly when applied to historical or culturally specific materials. These limitations make human judgment more important, not less. The future of AI in Cambodian education will depend on whether institutions cultivate a generation of students who treat these tools as objects of inquiry, not just instruments of convenience.

The Khmer script has always carried more than phonetic value. It encodes ritual, memory, lineage, and a quiet endurance. Its survival into the digital age is not guaranteed by technical progress alone. It depends on how Cambodian students choose to use, challenge, and build upon the systems that now render their language into code.

The Trellis AI Research Skills Enrichment Course helps students engage with these questions directly. Through practical training in bilingual workflows, students learn to integrate Khmer and English materials into their research while developing the skills to critique and shape the tools themselves. In doing so, they do not just adapt to a changing landscape. They begin to shape it.

Trellis Academic

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Contacts

+855 (0) 15 932 188

info@trellisacademic.com

Subscribe to our newsletter

Privacy Policy

© 2025 Trellis Academic. All rights reserved.